Interview - Meet Phil Davis by Dale Bert

Published in The OPEN ROAD for Boys - February 1948

Meet Phil Davis

YOU MAY BE one of the many who think Mandrake the Magician is just about as good a comic strip as there is. In that thought you'd share the opinion of Phil Davis, who draws the strip. Phil believes you like Mandrake because it isn't really a "cartoon" with exaggerated bodies and distorted positions, but rather, good finished artwork, properly proportioned. Not that Phil has any grudge against cartooning and caricature. He just can't do that sort of thing, and it makes him feel good to know there are plenty of people who appreciate what he calls "good literal drawing."

Mandrake the Magician was created back in 1934, when Phil was doing art work for an advertising agency in St. Louis. One of his buddies there was a copywriter named Lee Falk, who used to read all the comic strips, and one day he said to Phil: "Did you ever notice, there's no comic strip with a magician as the principal character ?" Phil replied that he hadn't noticed, but what of it? Falk went into a pep talk and convinced Phil there was a big market waiting. He was willing to write the continuity, and would make a trip to New York to sell the new strip. If Phil would draw the usual two-week series to be submitted. Phil was willing to try his hand and the first Mandrake went down on paper. Falk went to New York, made one call on King Features Syndicate, and Mandrake was sold. The New York Evening Journal commenced publishing Mandrake on June 11, 1934.

This sort of experience is highly unusual. It happened only once in a long time, but it shows that even with a highly-competitive market and plenty of cartoonists wanting to sell their strips, a fellow can come in with a brand-new idea and a new art technique - and sell it right away. Other papers started picking up Mandrake, and after a year of daily strips, the Syndicate ordered a Sunday page also. Mandrake has kept growing ever since.

Phil Davis was born in St. Louis on March 4 1906. He liked to draw from the time he was a small boy. During a summer vacation when he was 12 years old - that was during the first World War - he got a job as a tool boy in the Liberty Motors plant. There he met Franz Berger, who used to be captain of Purdue University's baseball and football teams. Berger was a mechanical engineering professor at Washington University - also doing a war job during the summer - and he encouraged Phil to take a manual training course at high school. Phil did, with every hope of becoming an engineer.

But when he graduated from Soldan High School, his family was in financial trouble, and he had to get a job right away. Because of his training in mechanical drawing he was able to work for the telephone company as a draftsman.

Then young Davis hit a series of bad luck streaks. He'd been sick in the flu epidemic, and had a form of sleeping sickness as an after-effect. The phone company had to transfer him to outside work - switch-board installation - but the continuing effects of the sleeping sickness made him undependable and he was laid off.

Phil tinkered with radio and got a first-class ham license (9 EDD). He took night-school courses in trigonometry and drafting, and finally hooked up with a civil engineering firm, where his lettering work was very much admired. One day the head draftsman said, "Why don't you try commercial lettering? There's a lot of money in that!" Phil took a Y.M.C.A. course in showcard lettering, and bought all the books on the subject that he could find. And through a series of small art jobs, he finally landed in the advertising agency where he met Falk.

"I didn't have any idea of the amount of work involved in a comic strip," Phil recalls. "I nearly killed myself in Mandrake's first year-working 14 hours every day, and 5 hours on Sunday besides! There's a lot of difference between taking a week to do one drawing for an advertisement - and doing 24 complete drawings for six comic strips! "Still, I wouldn't go away from my anatomically correct figures to do the faster type of cartoon illustration. Anyway, once you start a strip, the Syndicate wants it to be always exactly the same. "But all this pressure has had its advantage. By doing good art for Mandrake, I don't lose my touch, and I can always do commercial work in addition. I find that Mandrake has made me a better artist, and a much faster worker."

Phil Davis has a studio in a downtown office building, another in his home, and a couple of drawing boards in his country house in the foothills of the Ozark mountains. He isn't temperamental at all, and does his work at whichever of the three places he happens to be.

Drawing Mandrake may be a little easier for Phil, because he doesn't have to worry too much about the story. The stories - the trade name is "continuities" - are all written by Lee Falk, who lives in New York now, and mails two or three months' supply at a time to Phil. Phil studies the script, edits it a little, cuts down the amount of talking the characters do (on account of space limitations) and proceeds to rough out in pencil.

When he has six strips finished this way, he sends them over to a lettering man who inks in all the lettering. Sometimes a balloon will take more or less space than Phil had estimated, and with the lettering in first, he can adjust the drawings to fill the panels properly.

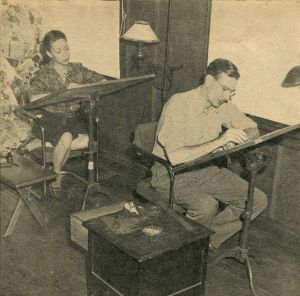

Nowadays, Phil has a real assistant - his wife, Martha, who used to be a fashion illustrator for St. Louis department stores. During the recent war, Phil felt that he ought to help, and did some work in preparing instruction manuals at the Curtis plant. Martha started working on Mandrake. "And now," says Phil, "she's just as good as I am! After the war, she didn't want to leave Mandrake - so now we work together, and each of us can do any part of the job, or finish the work of the other one."

Phil Davis stands 6 feet 4½ inches tall (yes, he was on the basketball team at Soldan) and weighs only 175 pounds. He has a little mustache, chestnut hair that's wavy on the ends, and brown eyes. He wears glasses only when he's at the drawing board. "I'm the laziest guy in St. Louis." He says. But he doesn't really mean that, because he has a complete power-tool woodworking shop in his country house, and he has done most of the cabinet work, plumbing and electrical work out there. He likes to swim in the river and lake behind his property. Do a little hunting, and play with his two dogs: Julius, a French poodle and Max, a dachshund.

Phil doesn't think he should give suggestion to young men. "I don't think there's any fixed formula that two different people can follow." He says, "because everybody learns differently. I'd say that all education is good, but in my opinion art education would take some of the freshness away from natural cartooning ability." If a fellow's got a touch and a technique of his own, he should certainly develop that individually, and not try to follow somebody else's pattern !"